The Network Effect: Why Human Connection Needs to Scale Beyond Dunbar's Number

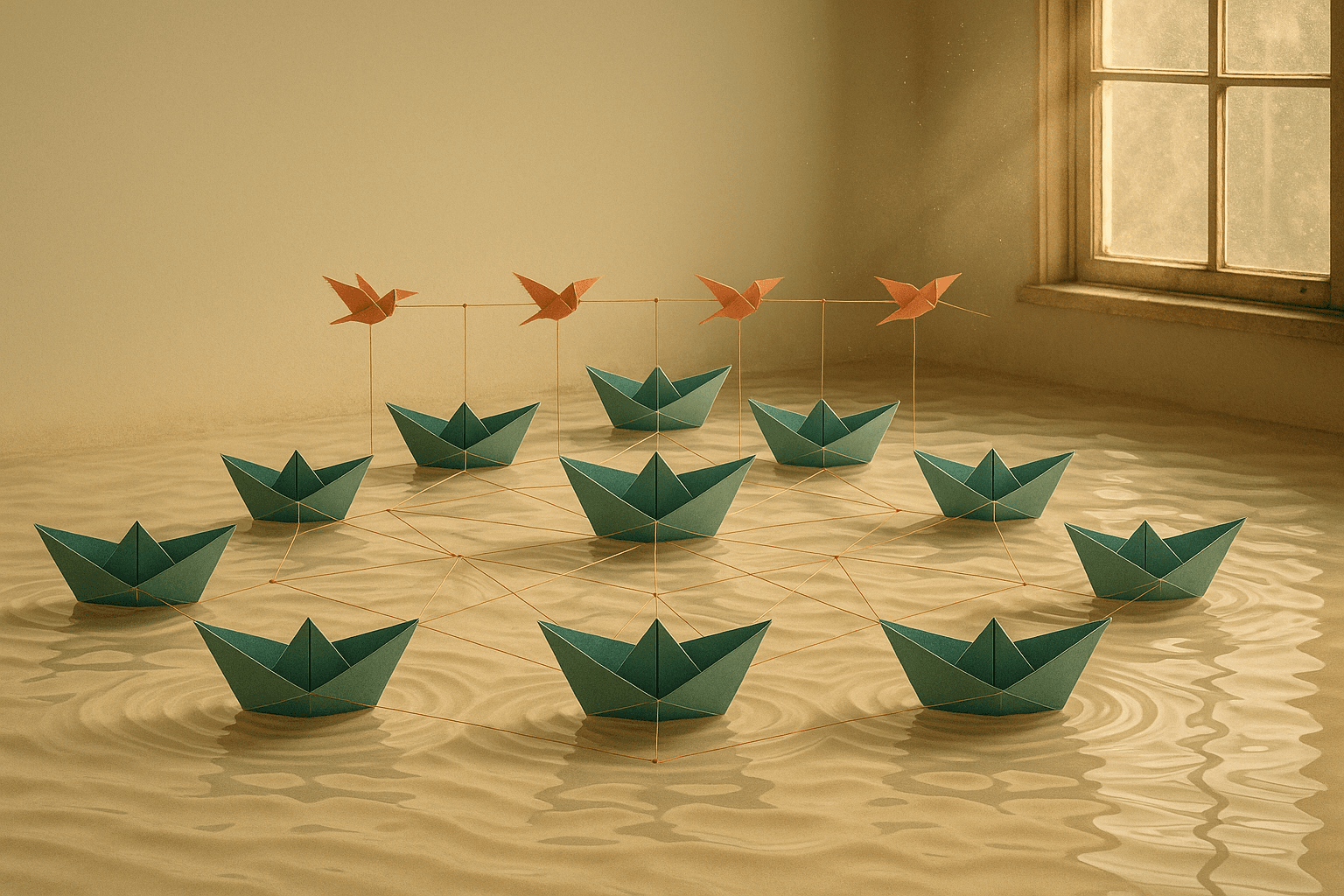

The notion that human communication should be constrained by evolutionary psychology's neat circles misunderstands what makes our species exceptional: our ability to cooperate and innovate at scales that transcend biological programming. While Dunbar's number might describe our capacity for intimate relationships, treating it as a ceiling for human connection ignores the transformative power of weak ties, bridging capital, and collective intelligence that emerge when we communicate beyond our immediate tribes.

Weak Ties, Strong Outcomes

Sociologist Mark Granovetter's groundbreaking work on weak ties revealed that our most valuable opportunities - jobs, innovations, and insights - often come not from close friends but from distant acquaintances and loose connections. These bridging relationships, which connect disparate social clusters, serve as conduits for novel information and resources that would never circulate within tight-knit groups.

The Linux operating system, powering everything from smartphones to supercomputers, emerged from thousands of developers collaborating online without ever meeting face-to-face. Wikipedia marshals millions of editors to create humanity's most comprehensive encyclopedia. These achievements required communication far beyond 150-person circles - they demanded open networks where strangers could contribute expertise, catch errors, and build on each other's work.

Research on innovation networks demonstrates that breakthrough ideas emerge at the intersection of diverse knowledge domains. Companies with executives maintaining broad, weak-tie networks consistently outperform those whose leaders interact primarily within closed circles. The very innovations that critics use to decry social media - from the internet itself to the devices we access it on - emerged from expansive collaboration networks, not intimate groups.

Voice to the Voiceless

Before social media, marginalized communities faced insurmountable barriers to public discourse. Media gatekeepers determined whose stories mattered. Political and economic elites controlled narrative framing. Geographic isolation prevented coordination among dispersed groups sharing common struggles.

The Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo didn't emerge from 150-person groups having measured conversations. They erupted when millions found their private experiences reflected in public testimony, when isolated incidents revealed systemic patterns, when the previously voiceless discovered they constituted a majority.

Research on social movements shows that successful activism requires both strong ties for sustained commitment and weak ties for rapid mobilization. Digital platforms enable movement leaders to maintain core organizing groups while simultaneously reaching sympathizers who contribute through small acts - sharing content, donating money, showing up for single events. This hybrid structure, impossible without scaled communication, has driven more social change in the past decade than the previous century of top-down organizing.

For transgender youth in rural areas, online communities provide literal lifelines. For workers facing exploitation, social media enables rapid information sharing about employers and organizing across locations. For patients with rare diseases, global networks connect those who would never find sufficient support within Dunbar-sized groups.

The Democracy of Information

Critics worry about misinformation spreading through expanded networks, but this concern obscures how closed communication circles historically enabled far worse distortions. Before mass communication, local elites could maintain power through information monopolies. Isolated communities fell prey to unchallenged prejudices. Scientific and medical knowledge remained locked in ivory towers.

The same connectivity that spreads false rumors also enables rapid fact-checking. Studies of online civic engagement reveal that people exposed to diverse information networks develop more nuanced political views than those in homogeneous communities. Yes, echo chambers exist online, but they're often less hermetic than physical communities where geography, class, and race create nearly impermeable boundaries.

Consider how quickly COVID-19 vaccines were developed through unprecedented global scientific collaboration. Researchers shared genomic sequences, clinical data, and experimental results in real-time across institutions and borders. This radical openness - antithetical to Dunbar-limited communication - compressed decades of normal development into months.

Collective Intelligence at Scale

Human groups demonstrate emergent intelligence properties that transcend individual capabilities, but only when they achieve sufficient size and diversity. Studies show that problem-solving performance improves with group size up to surprisingly large numbers - well beyond 150 - particularly for complex challenges requiring diverse expertise.

Online prediction markets aggregate information from thousands of participants to forecast events more accurately than expert panels. Citizen science projects like eBird or Galaxy Zoo harness millions of observers to generate datasets impossible for professional researchers alone. These aren't intimate collaborations but loosely coordinated swarms that achieve through scale what no small group could accomplish.

The argument that people "aren't meant" to communicate at scale fundamentally misunderstands human nature. We're the species that developed language, writing, printing, and telecommunications precisely to transcend the limits of face-to-face interaction. Each expansion of our communication capacity has coincided with leaps in knowledge, prosperity, and human rights.

Managing Scale Without Restricting Voice

The real challenge isn't that people communicate too much, but that our platforms optimize for engagement over understanding. The solution isn't to restrict human connection to arbitrary evolutionary limits but to design systems that support meaningful interaction at multiple scales simultaneously.

Successful online communities already demonstrate this. They maintain core groups for deep engagement while enabling peripheral participation from much larger audiences. They use moderation, reputation systems, and algorithmic curation not to limit speech but to surface signal from noise. They recognize that different types of communication serve different purposes - intimate sharing, information broadcast, collaborative work, public discourse - and create appropriate contexts for each.

Some argue that online communication's problems stem from removing traditional intermediaries, but this misses how those gatekeepers systematically excluded marginalized voices. The challenge is creating new forms of mediation that enhance rather than restrict human connection - systems that help us navigate abundance rather than enforcing scarcity.

Beyond Biological Determinism

Dunbar's number describes one aspect of human social capacity, not its entirety. We also possess remarkable abilities for abstract reasoning, symbolic representation, and cultural transmission that allow us to coordinate across vast networks through shared narratives, institutions, and technologies. To suggest we should communicate only within biological constraints is like arguing we should travel only as far as we can walk.

The disruptions caused by expanded communication are real, but they're growing pains of a species learning to collaborate at planetary scale. Climate change, pandemics, economic inequality - none of these challenges respect Dunbar's boundaries. Their solutions require coordination among billions, not hundreds.

Rather than retreating to the comfortable confines of small-group communication, we need to develop new literacies, norms, and technologies for productive interaction at scale. The answer to democracy's challenges isn't less democracy but better democratic processes. The answer to information overload isn't information restriction but improved information management.

Human progress has always involved transcending biological limitations through cultural and technological innovation. The ability to maintain meaningful connections beyond our immediate tribe isn't a bug of modern technology - it's the feature that enables science, democracy, and the vast cooperative enterprises that define human civilization. Our task isn't to restrict this capacity but to wield it more wisely.

Citations

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]

- [4]

- [5]

- [6]

- [7]Educate, Empower, Advocate: Amplifying Marginalized Voices. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 2019

- [8]

Comments